Kokusai Batto-Do Rengo-Kai

Shihan Demura brought Batto-Do into the public's awareness.

The Batto-Do techniques practiced by members of the International Batto-Do Rengo-Kai (Alliance) and the Society for the Preservation of Toyama-Ryu Batto-Do have a long history. It includes techniques and variations of techniques used by the Samurai as well as modern era Japanese

The name Toyama-Ryu comes from the military school at which these techniques were codified and studied by the Toyama Military Academy. Officially known as the Rikuguin Heigakko-Ryu Toyama Gakko Shucho-Jo, it was formed as a branch school for Army officers in 1873. It was modeled after European military academies such as the French and Prussian military academies. Early students trained in a variety of studies related to military tactics and such skills as Kendo, Judo, horsemanship, marksmanship and physical training. It is also interesting to note the school was the home for the Army's school of music, and that students were also trained as military musicians. In 1875, the school became the Japanese Army's Military Preparatory School and came under control of the Army Ministry.

Prior to World War II, the Toyama Academy was renowned as a school which produced outstanding officers who were exceptionally physically fit. The Academy had many quest instructors, some of whom had been samurai prior to the Meiji Restoration. Two famous kendo instructors at the school were Takano Sasaburo and Nakayama Kakudo. In addition to his kendo expertise, Nakayama Sensei was a recognized expert in Omori-Ryu Iaido, and the head of the Shimomura-ha branch of Muso Jikiden Eishin-Ryu Iaido. Nakayama Sensei greatly influenced the swordsmanship training at the Academy. Nakayama Sensei would later go on to found one of the most widely practiced styles of Iaido today, the Muso Shinden-Ryu.

At the Academy, the study and use of practical cutting techniques from the old Koryu was emphasized. A review of the advanced techniques of the Omori-Ryu, the Mugai-Ryu and especially the Batto-Do techniques of Eishin-Ryu taught at the Academy by Nakayama Sensei clearly shows the basis for the techniques practiced in Batto-Do today.

It is generally held that the official formation of the Toyama-Ryu was in 1925. According to Sensei Nakamura Taizaburo, the techniques codified were agreed upon by a committee of senior fencing instructors at the Academy and given the name Toyama-Ryu Kata as well as descriptions for Omori and Eishin-Ryu Kata. A training manual from 1944, the Gunto no Sho, shows seven Kata as well as a section on tamashigiri (test cutting). Nakamura Sensei later added an eighth and final kata. These techniques were taught to the Officers at the Academy until the surrender of Japan at the end of World War II. After the World War, the practice of these techniques, along with the practice of all martial arts, was prohibited by the Occupation Forces in Japan until the ban was lifted in 1952.

The individual most responsible for the renewed interest in Toyama-Ryu techniques is Nakamura Taizaburo. Nakamura Sensei was a graduate of the Toyama Academy, and was also a Special Battlefield Ju-Ken-Do Instructor for Japanese soldiers during World War II. In 1952, after the martial arts proscription was lifted, Nakamura Sensei once again began to teach Toyama-Ryu Iaido. In 1977, Nakamura Sensei, along with another former instructor at the Toyama Academy, Masudo Hideo, formed the all Japan Toyama-Ryu Iaido Federation. A renowned kendo and Iaido instructor, Nakamura Sensei was awarded Hanshi and 10th Dan by the Kokusai Budoin. In spite of this great honor, Nakamura Sensei was always ready to point out that the Toyama-Ryu Iaido was found by committee, and therefore had no one founder or "Soke". Nakamura Sensei would continue to work tirelessly for the promotion of Batto-Do. After many years of study, Nakamura Sensei left the All Japan Batto-Do Federation and founded his own style, Nakamura-Ryu. Even in his later years, Nakamura Sensei worked and traveled worldwide to promote Batto-Do.

Nakamura Sensei taught in a number of Dojo in Japan. One of these was the Dojo of Sakagami Ryusho. In addition to his expertise in Shito-Ryu Karate, Sakagami Sensei was an expert practitioner in Kendo and Iaido. At Sakagami Sensei's Dojo, Nakamura Sensei taught Kendo and Iaido including the techniques of Toyama-Ryu Iaido. It was during this time that Nakamura Sensei began to teach the president and founder of the International Batto-Do Rengo-Kai (Alliance) in the United States, Sensei Fumio Demura. Demura Sensei continued his studies in Kendo and Iaido with Nakamura Sensei until Nakamura Sensei passed away on May 13th, 2003 at the age of 92.

In the 1980's, Demura Sensei began to invite senior Batto-Do instructors to the United States to help provide proper instruction in the techniques of Toyama-Ryu Iaido. In 1989, Nakamura Taizaburo Sensei came to the United States to see the progress that had been made. After this visit, Nakamura Sensei formally recognized Demura Sensei as a Senior Instruction for Toyama-Ryu. After his death in 2003, the Kaicho (president) of the All Japan Batto-Do Federation, Ueki Seiji, began to make regular visits to the United States and Demura Sensei's Dojo to help promote the correct study of Toyama-Ryu Batto-Do.

After Nakamura Sensei's visit in 1989, Demura Sensei formed the International Batto-Do Rengo-Kai (Alliance). This Alliance maintains the teachings of the Toyama-Ryu and the All Japan Batto-Do Federation in Dojos around the world. Visiting instructors from the All Japan Batto-Do Federation continue to make regular visits to Dojo within the Federation to ensure quality instruction. Members of the IBR Dojos also make regular trips to Japan for competition and instruction from the Senior instructors there.

It is the desire of the members Internatoinal Batto-Do Rengo-Kai (Alliance) that these techniques, with their centuries old tradition of battlefield effectiveness not be lost. It was the desire of Nakamura Sensei, and is the desire of Demura Sensei, that the study of these techniques, along with the moral correctness that pervades them makes the practitioner a better person. For it is in this training that we learn to "cut" away the actions and attitudes that are detrimental to ourselves, our family, and our society. These are the goals of a true practitioner of Batto-Do.

Logo Meaning

The circle surrounding the logo is Wa, which means Peace.

Tozai Nanboku International Unity and Peace.

The Attributes of Good Character.

The red in the logo represents the love we have for each other.

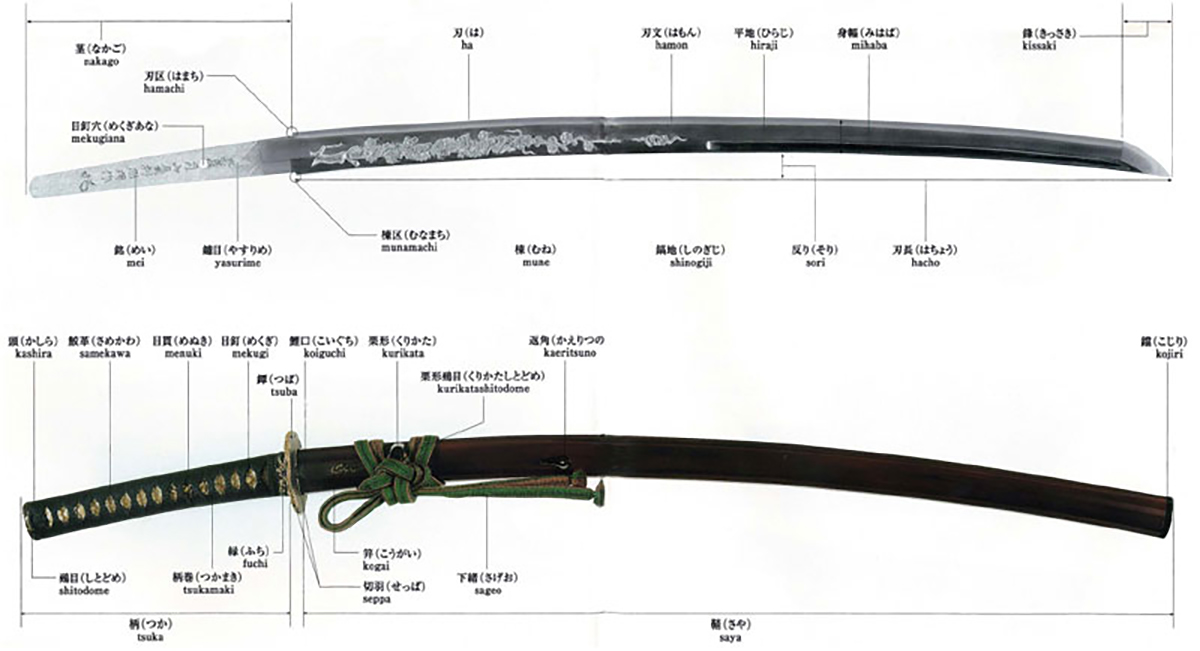

The Sword

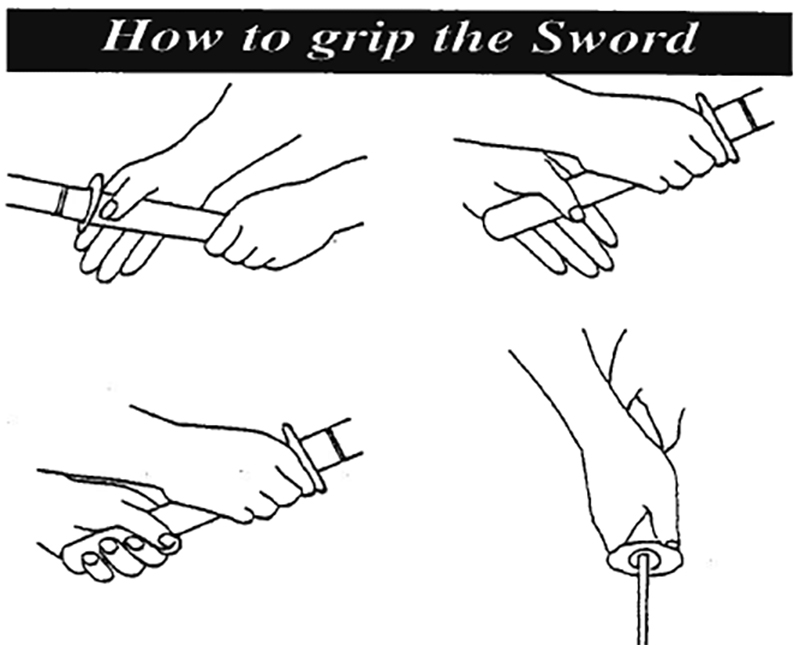

Batto is an actual cutting sword that is used in practice to cut, at a predetermined angle, bamboo or straw, which has been immersed in water for several days. This is similar to Iai-Do in that form is practiced without actual cutting. This technique practices from, accuracy and timing to increase skip and strength.

Batto is an actual cutting sword that is used in practice to cut, at a predetermined angle, bamboo or straw, which has been immersed in water for several days. This is similar to Iai-Do in that form is practiced without actual cutting. This technique practices from, accuracy and timing to increase skip and strength.

The use of the sword was originally meant for killing people, but after the 14th century, the Shogun Ieyusu Tokugawa created Edo Era. Since his control of Japan, peace was restored, so therefore the use of the sword changed from killing opponents to saving people, protecting self, and it was used for the purpose of self-discipline and mind and body exercise. That way it changed from a killing sword to a living sword.

After World War II, Kendo and Iai-Do changed to more of a sport which led to a few problems, since the philosophy behind the training is that, without the true feeling of the sport, it’s no different than just playing baseball or running. I think the way of the sword is much more valuable than that. The way of the sword is clearly understood as "Live or Die;" therefore the art of the true cutting is the center of Kendo and Iai-Do. Bamboo fighting or no-partners and cutting-air form of Iai-Do cannot get the true feeling of cutting; you can only get this experience from Batto-Jutsu.

Download Sword Booklet

The Parts of the Sword

Batto Nou-Tou Selections

Nou-Tou is the Japanese term for replacing the sword in the saya.

There are seven main types of Nou-Tou that we use and are demonstrated by the images below.

Hiki Nou-Tou - The "Regular" Nou-Tou, generally done after a Chiburi.

Hasami Nou-Tou - The "Pinch" Nou-Tou.

Migi Gyaku Nou-Tou - Reverse Nou-Tou, sword to the right.

Hidari Gyaku Nou-Tou - Reverse Nou-Tou, sword to the left.

Kotegaeshi Nou-Tou - Flip Back Nou-Tou.

Yoko-Beki Nou-Tou - Similar to Hiki Nou-Tou, but done from a side position..

Higi-Agi Nou-Tou - Pull back towards ear with edge up.

Batto Katas

SUI SHIN RYU NO KATA

Download Sui Shin Ryu no Kata

Hakama FAQs

When can I wear a hakama?

It depends upon the rules or conventions of your organization or dojo, or of one you may be visiting, so you should find out what those are. Many types of arrangements exist today. Some associations reward attainment of a certain rank with the privilege of wearing a hakama, while others view the hakama as an integral part of the training uniform from day one. In some dojo, hakama-wearing is a function of gender and/or rank, and in yet others, it is left to personal choice and may symbolize an individual’s personal commitment to a path of study.

Why do I see some people wearing black hakama and others wearing dark blue?

You can never go wrong with basic black, so if you are planning to travel and visit unfamiliar dojo, you will do well to outfit yourself with a black hakama. Otherwise, the custom and convention in your dojo is what you should pay attention to. Often, the color choice has no significance whatsoever and is simply a matter of personal preference. However, in some cases, color may be used to subtly distinguish newer students from "seasoned" ones, with the newer students wearing black and the more experienced ones wearing blue or black, their choice. White hakama are sometimes used in various arts or for certain occasions.

What should I look for in a hakama?

Your hakama is in for a lot of wear and tear, especially if you train hard and often. Overall, you should look at several key areas.

• The fabric. Flimsy fabric has a short, sad. Go for sturdy, tightly woven fabric you can depend on to last, and check shrinkage and care instructions.

• The construction. The way the hakama is put together is just as important as the fabric. Look for strong thread, tight stitches, and straight reinforced seams that will hold the hakama together against the rigors of training (like when someone steps on your hem just as you are launching into a high fall!).

• The koshiita. If your hakama has a traditional style koshiita, you won’t want a backing of cardboard or brittle plastic; look instead for rubber or vinyl, which are more durable and flexible.

• The himo. Be sure both the front and back himo are sufficiently long to wrap securely around your waist and hips. And if you are an aikido student, be sure you don’t need to tie a knot in the back, where you might roll on it.

• The fit. Look for comfort and fit, too, because these are safety factors. Your hakama should not bind in any way and should hang loose and straight over your hips. Bu Jin offers a wide range of sizes, including a women’s version, that will accommodate the "average" figure as well as the "not so average" figure.

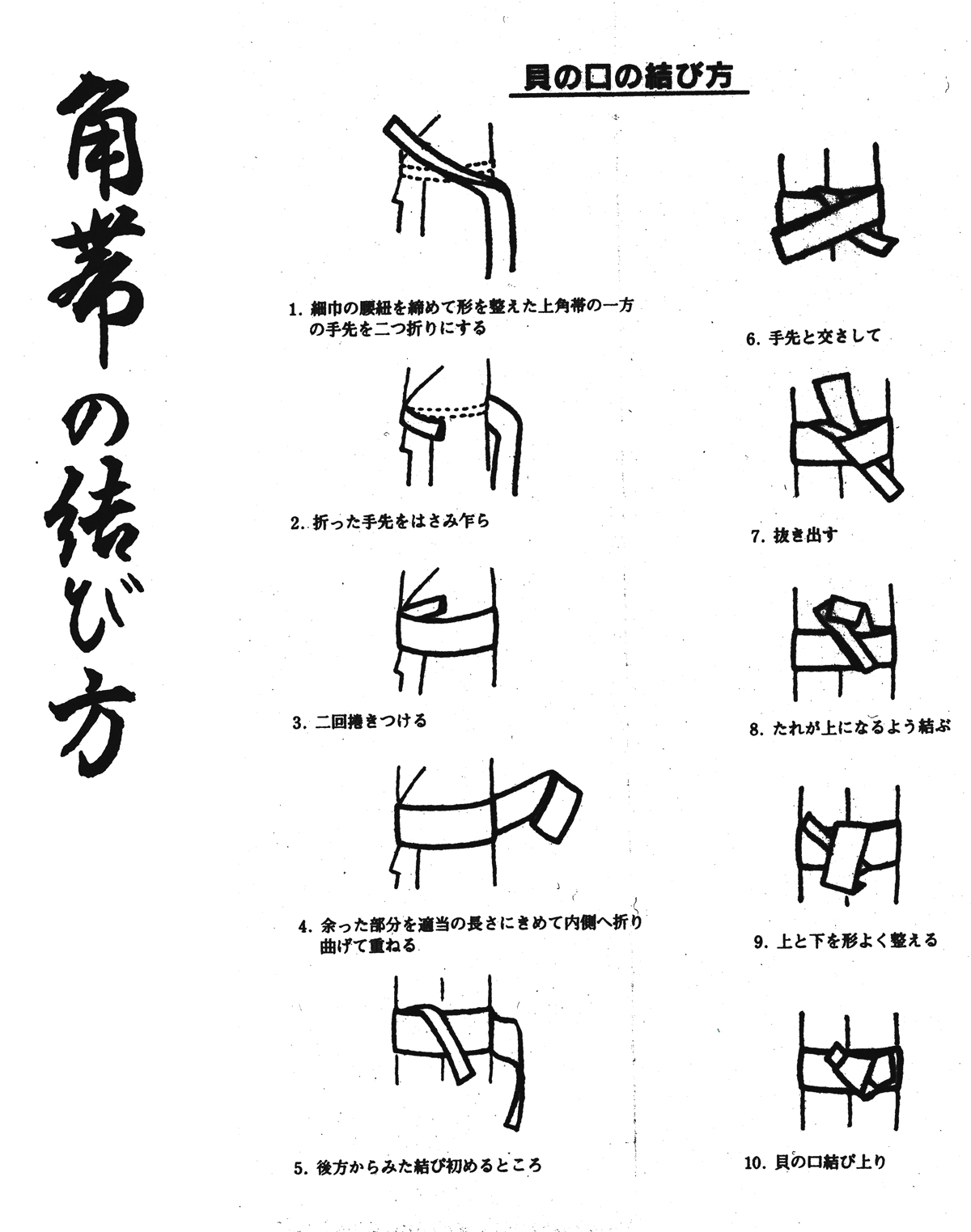

Instructions on How to Fold Obi (Belt) Under Hakama

How long should my hakama be?

You can wear your hakama at whatever length you find most safe and comfortable. Today in martial arts, the trend is for the hakama to fall somewhere around the ankle, but It really depends on the custom of your art or dojo. Kendo, jujutsu, and kenjutsu practitioners tend to prefer somewhat shorter hakama, whereas some aikido practitioners choose a longer length. We suggest that If at all possible, before you buy your first hakama, borrow a friend’s to try on and move around in. It is best if you borrow someone’s whose hip bones are about the same height from the floor as yours. Tie on your obi, and then put on the hakama and do some warm-ups and stretches, take a back-fall on the carpet and so on. You might repeat this process a time or two, with your obi tied at different places around your hips/waist. Determine the resting-place for your obi and hakama, and then from there, you can go on to the next step of determining the length.

How should I tie my hakama on?

Good question, and perhaps the most often asked. Trying to devise a satisfactory set of written instructions for hakama tying is like trying to explain relativity … well, almost. Seriously, for now, the best method of transmitting the secrets of hakama tying is still the traditional sempai-to-kohai method, "Ask a senior student." There is no definitive way to tie on a hakama, since different arts have different requirements. Kendo and iaido practitioners, for example, often tie the back on first and then the front, while Aikido practitioners commonly do the reverse, finding that the hakama stays on better for taking ukeml. So start with your friendly sempai.

How should I fold my hakama when I’ve finished training?

The folding of your hakama following training can serve as a cooling down period, a time to reflect while performing a repetitive, somewhat meditative task. It also serves to keep your hakama looking good by sharpening the pleats, flattening out the himo and so on, making it ready for your next session on the mat. While there are a number of folding methods, here is a traditional one that works well: